Let’s use one example review: “The movie was not good.” A human instantly knows this is negative. The tricky part is that the word “good” is usually positive, but “not” flips its meaning. Any model that treats words as isolated signals can get confused here. The whole story is about giving the model a way to represent “good, but negated.”

In the older approach, we often tried to turn the entire sentence into a single fixed-size vector and then classify it. A simple way is to start with a vocabulary and represent the sentence by counts: how many times each word appears. For our tiny example vocabulary [movie, not, good], the sentence “The movie was not good” becomes the vector x = [1, 1, 1]. This vector is easy to feed into a neural network, but notice what it loses: it does not encode word order. The vector for “good not movie” would be the same. That is the first weakness of the old pipeline for language: many different sentences collapse into the same numbers.

Now we can run an “old” classifier. We apply a weight matrix W and bias b to the input vector x, producing a score z: z = Wx + b. If we use just one layer for simplicity, z is a single number. Then we apply a sigmoid: p = sigmoid(z), which squeezes any real number into a probability between 0 and 1. Finally we pick a threshold like 0.5. If p ≥ 0.5, we predict “positive,” otherwise “negative.” This structure is clean and powerful, and stacking more layers can help the model learn more complex patterns. But there is still a core problem: because the input x does not explicitly represent that “not” modifies “good,” the model must guess that relationship indirectly, and it can easily fail when sentences get longer or phrasing changes.

To see the limitation more clearly, imagine the sentence “The movie was good.” Under the same count-vector idea, with vocabulary [movie, not, good], that becomes [1, 0, 1]. The only difference from [1, 1, 1] is the extra “not” count. The model could learn that “not” is a negative signal, but it still does not truly model the idea that “not” attaches to a specific word. In real text, “not” might be far away (“The movie, despite the great actors, was not good”), or it might appear in more complex patterns (“not only good but great”). The old approach tends to treat language like a bag of ingredients, not a structured message.

Transformers start from a different idea: do not crush the sentence into one vector too early. Keep the sentence as a sequence of token vectors, and let the model decide how the tokens relate. We begin by turning each word into an embedding vector. Think of this as giving each token a learned meaning in vector form. For our sentence, we have vectors e_{\text{movie}}, e_{\text{not}}, e_{\text{good}}. We also add position information so the model knows which word comes first, second, and third.

Now the transformer applies attention, which is the heart of the method. Attention lets each token look at every other token and decide what matters. The math looks like this: the model creates three versions of each token vector using learned matrices: queries Q, keys K, and values V. For the whole sentence (all tokens at once), attention is computed as

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax((Q · Kᵀ) / √dₖ) · V

Here is the meaning in plain steps. First, QK^\top creates a table of similarity scores between tokens: how much token i should pay attention to token j. Second, softmax turns each row into weights that add up to 1. Third, multiplying by V produces a new vector for each token that is a weighted mixture of information from other tokens.

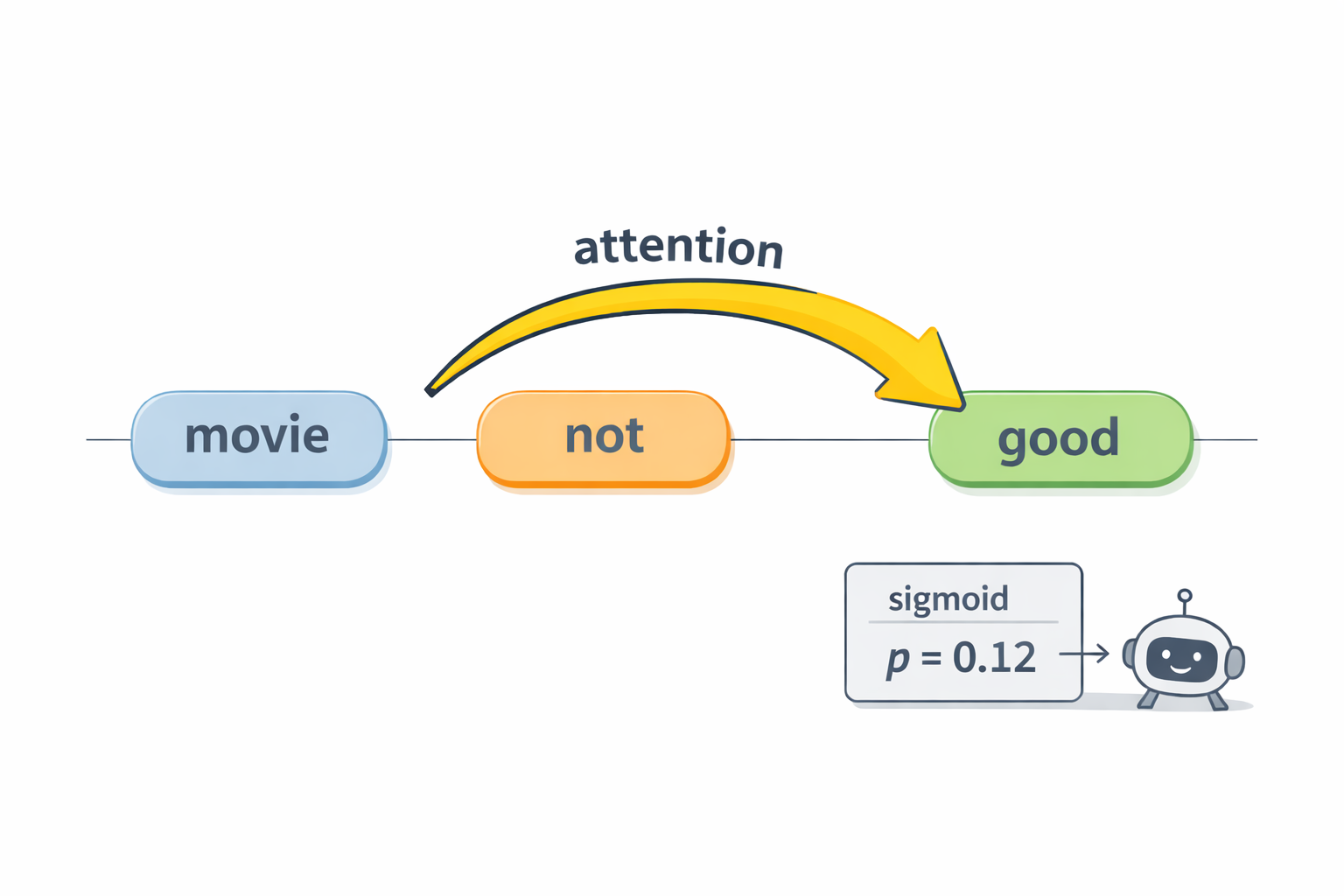

Let’s apply that idea to our single example. In “The movie was not good,” we want the representation of “good” to incorporate “not.” Attention makes this possible in a direct way. When the model computes the attention weights for the token “good,” it can assign a strong weight to the token “not.” That means the updated vector for “good” becomes something like “good, influenced by not.” In other words, the model can build a context-aware meaning: negated-good, which is much closer to what humans understand.

After several transformer layers, we need one vector that represents the whole sentence so we can do binary classification. A common trick is to use a special summary token at the start (often called [CLS]). This token also participates in attention, so it learns to gather information from the whole sequence. At the end, we take the final vector for that summary token, call it h, and feed it into a familiar classifier head:

p = sigmoid(wᵀh + b)

This is the same sigmoid probability step as before. The difference is what h contains. In the old approach, h was built from a collapsed input vector that lost structure. In the transformer approach, h is built after many rounds of tokens interacting through attention, so it can encode relationships like “not modifies good.”

So why do transformers feel like “the thing we use now”? It is because attention provides a strong and flexible way to model relationships inside data. Language is full of relationships: negation, emphasis, references, cause and effect, and long-distance connections across a paragraph. Transformers do not need you to manually invent rules for these patterns. They can learn them from examples, because attention gives them the mechanism to connect the right pieces together.

In our single review, both approaches end with the same kind of decision: a sigmoid gives a probability, and a threshold gives yes/no. The real upgrade happens before that final step. The older vector-to-sigmoid pipeline can work, but it often struggles to represent meaning that depends on word interactions. A transformer is built specifically to learn those interactions. That is why, for text classification problems like sentiment, spam detection, and toxicity detection, transformers usually perform better, especially when sentences are longer, phrasing is varied, or context is subtle.